Highlights:

- IIM-Ahmedabad alumnus and telecom veteran to lead T-Mobile from November 1, following Mike Sievert’s promotion to vice-chairman.

- ANI Editor posted the update on X, highlighting yet another India-born executive taking charge of a Fortune 500 company.

- Social media user Aravind argued Indian-born CEOs are “docile and servile,” making them safe, compliant choices for global boards.

- Aravind pointed out that India-born leaders rarely speak out on issues affecting Indians — from H-1B visa hikes to racial attacks.

- The post sparked discussion about why India-born CEOs dominate over US-born Indian Americans, with suggestions that boards prefer leaders who avoid political controversy.

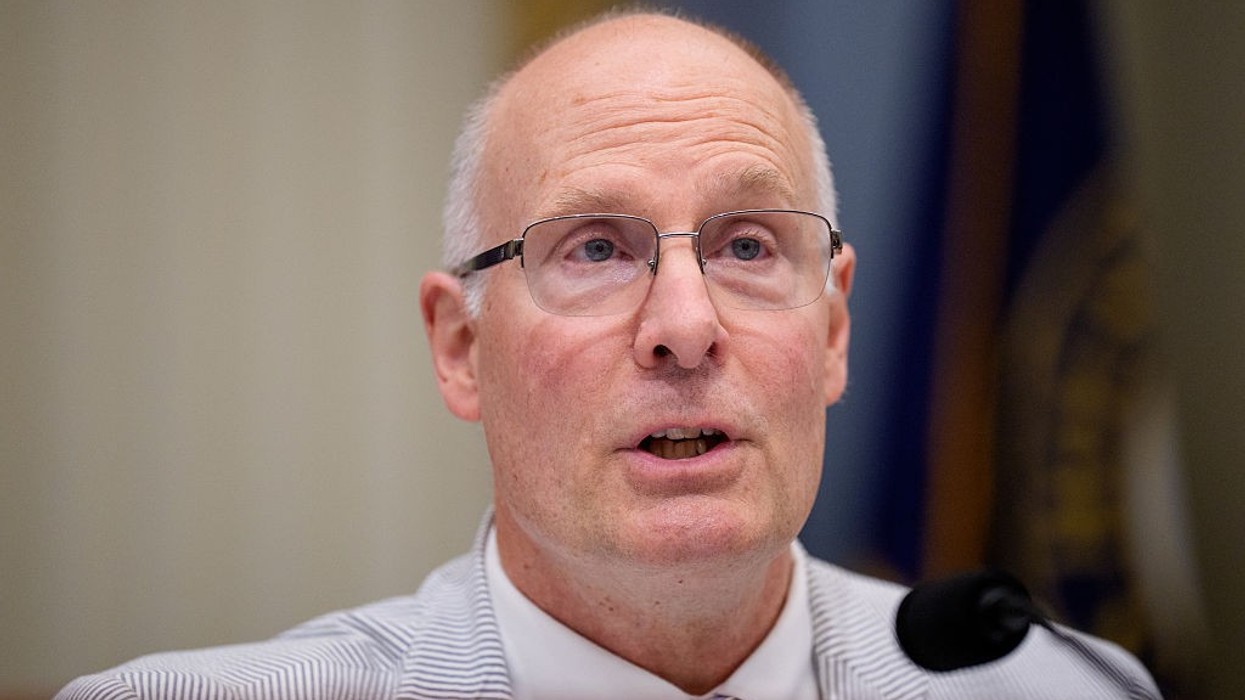

When Times of India reported Srinivas (Srini) Gopalan’s elevation as the new CEO of T-Mobile in its “Beer with US” column, the story seemed like yet another addition to the growing list of India-born executives helming America’s largest corporations.

Gopalan, an alumnus of IIM-Ahmedabad and industry veteran with experience at Hindustan Unilever, Bharti Airtel, Vodafone, and Deutsche Telekom, will take charge of the $81 billion telecom giant on November 1, succeeding Mike Sievert. The move puts him in the company of Satya Nadella, Sundar Pichai, Arvind Krishna, and others who have become symbols of Indian excellence abroad.

Smita Prakash, Editor of Asian News International (ANI), shared the article on social media, highlighting the achievement and implicitly celebrating India’s global corporate footprint. It was the kind of news Indian audiences typically cheer — proof that India produces leaders who can take on the highest echelons of global business.

But not everyone joined the applause. Aravind, a popular and provocative Twitter commentator known for his sharp, contrarian takes, offered a strikingly different perspective. In a long thread, he suggested that the rise of India-born CEOs is not merely a story of talent and merit, but also of temperament.

Social media reacts

“My theory is that they’re chosen because they tend to be docile and servile along with all the great qualifications and qualities of a leader,” Aravind wrote, arguing that boards prefer India-born executives precisely because they are seen as “safe bets” who will not rock the boat politically or ideologically.

Aravind contrasted the relative silence of India-born CEOs on issues such as racial attacks on Indian immigrants and the recent $100,000 H-1B visa fee hike with the vocal opposition expressed by several White, Jewish, and Chinese-American leaders. “Indian origin leaders, on the other hand, are a safe bet for keeping their mouths shut in silence. For instance, they haven't yet posted a single line condemning racial targeting, attacks, or killings of Indians, or speak out against H-1B visa policy changes that hurt their own community – or even their own company,” he claimed.

He went further, suggesting that the “independent American spirit” found among U.S.-born Indian Americans makes them less likely to be chosen for CEO positions. “If it is really the race or culture that makes good CEOs,” he wrote, “then why don’t we see as many US-born Indian Americans with equally good credentials being appointed?”

Indian-born CEOs worth the catch

This reaction turned what was initially a feel-good corporate announcement into a broader conversation about representation, assimilation, and the expectations placed on Indian-origin leaders. For some, Aravind’s comments were a cynical attempt to tarnish a genuine success story. For others, it was a much-needed critique of how corporate power operates — rewarding leaders who are apolitical, uncontroversial, and willing to prioritize shareholder value above all else, even when their own communities are impacted.

The debate highlights a deeper tension: are India-born CEOs simply focused professionals who keep politics out of business, or does their silence on immigration, racism, and policy issues signal a form of self-censorship that boards find comforting? As MAGA-aligned hardliners increasingly target immigrants and foreign-born executives as “globalists,” the expectation that leaders like Gopalan might speak up for their communities could grow stronger — even if their boards prefer they do the opposite.

In the end, Srini Gopalan’s appointment is both a personal milestone and a symbol of India’s continuing rise as a supplier of global executive talent. But the conversation sparked by Smita Prakash’s tweet and Aravind’s thread suggests that for many observers, the real question isn’t just who becomes CEO — it’s how they choose to use their influence once they get there.

Let’s stop shaming Genzfor switching jobsI see a lot of ‘career gurus’shaming 22-year-olds for switching jobs every year.But isn’t that exactly what the youth should be doing? 🤔Early in our… | Anupam Mittal | 561 comments

Let’s stop shaming Genzfor switching jobsI see a lot of ‘career gurus’shaming 22-year-olds for switching jobs every year.But isn’t that exactly what the youth should be doing? 🤔Early in our… | Anupam Mittal | 561 comments