- Saturday, April 27, 2024

Nadeini Asbali on the challenges faced by hijab-wearing females in Britain

By: Sarwar Alam

IN her new book, author Nadeine Asbali reveals how her decision to wear the hijab led to an “overnight” shift from blending in to facing “racism and Islamophobia”.

Born in the UK to an English mother and a Libyan father, Asbali looked like the quintessential white British teenager before putting on the hijab.

However, her mixed-race background, with two different cultures, left her “confused” about her racial identity, she said.

“I felt not quite whole because I wasn’t fully English and I wasn’t fully Libyan. I felt English when we were in England and then we’d go to Libya every summer holiday for the whole six weeks, but the two never mixed until I started to get older,” Asbali told Eastern Eye.

“In my teenage years, my friends were doing the things teenagers do, like drinking and hanging out with boys. When I wasn’t doing that, that’s when I suddenly realised, ‘Hang on, I’m not actually English, I’m not actually like these people around me’.’

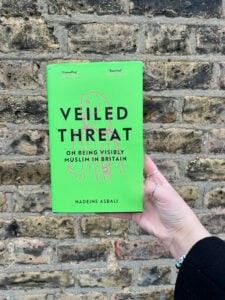

Her book, Veiled Threat: On being visibly Muslim in Britain, is part memoir, part political essay and delves into the hardships of growing up as a hijab-wearing woman in the UK.

Former prime minister Boris Johnson caused controversy with his comments that veiled Muslim women looked like “letterboxes” and “bank robbers”.

A 2019 Nottingham Trent University study reported that attacks against hijab-wearing women in the UK were on the increase, suggesting this was because veiled Muslim women were “represented as ‘agents’ of terrorism”.

Asbali said, “I start each chapter with an anecdote and then move into a political unpacking of that to weave between what I’ve been through and the wider systematic impact Islamophobia has had on visible Muslim women.

“It was a very cathartic journey for me and helped me process a lot of the trauma I went through, over the past decade and a half.”

In the book, Asbali discusses topics such as the online Muslim alt-right (or “akh-right”, as she puts it), white feminism and its “saviour” complex, the representation of Muslim women on screen and why Muslim women deserve control over their voices.

“I wanted to get across how Muslim women are considered a paradox, where we’re seen as these meek victims who are oppressed and need ‘saving’, but, at the same time, we’re seen as a threat. I wanted to get that across in the title.

“That’s why it’s so difficult being a Muslim woman, especially in the west, because half the people want to save you, while the other half want to criminalise you.”

Asbali, 30, admitted she didn’t have a very religious upbringing, but decided that “if I can’t be Libyan and I can’t be English, maybe I can try being Muslim”.

The hijab was her “ticket” to her Muslim side and, aged 15, Asbali wore it on her annual summer holiday to Libya.

On her return, at immigration at Heathrow, she was interrogated by border control officers – a first for her. Asbali’s brother, who looks “very English”, was let through without any questions. (The siblings travelled without their parents).

Asbali said of that experience, “It really hit me hard. But, also, teachers, when they first saw me wearing the hijab, called the names of other Muslim girls in the class because they just got us confused.

“On the school bus, this group of boys started shouting ‘Taliban’ at me. On other occasions you’d hear typical muttering under the breath about immigrants while you’re standing right there.

“It made me realise how hostile Britain is to visible Muslimness. I grew up in Northampton, which wasn’t and still isn’t very Muslim. After deciding to wear the hijab, overnight, I went from just kind of blending in to suddenly facing racism and Islamophobia.

“It made me quite resentful of Britain as I felt like I was being rejected by the only place I knew of as home.

“The negative reaction and almost being made an outcast made me forget my Britishness and embrace the Muslim, Libyan side of me.”

When Asbali was asked why she wore the hijab and what it meant to her, she realised she knew very little about Islam and set out to learn more.

“After learning and understanding, I believe the hijab to be compulsory in Islam. It’s important to be unapologetic and to show Britain, and the west, that we are part of Britain too, that Britishness is not just this one idea, it’s not just white, not just Christian. Society needs to accept that more than it has been.”

On the impact of toxic masculinity and a far-right version of Islam, Asbali noted the influence of personalities such as Andrew Tate on impressionable young Muslim men and how that can lead to misogyny.

“I tried to start a dialogue that’s often ignored by not only leaders in our community, but also teachers and those in charge of safeguarding young people. Issues such as the ‘akh-right’ and Andrew Tate are shooed away as a ‘Muslim problem’ when it’s so much more complicated than that. It should be more pressing that these young boys online are taking influencers from the akhright as idols and important figures in their developing relationship with Islam.”

In the book, Asbali explores how wearing a hijab impacts her daily life as a secondary school English teacher and journalist.

Asbali is now a columnist at the Metro, and has also written for The Guardian, the Independent and the New Statesman.

Asbali hoped she could inspire her young female Muslim students to feel confident to be themselves. “I hope the book gives the message that they can be unapologetically and visibly Muslim,” she said.

“But I also hope it gives other people an insight into what it’s like to be a Muslim woman and how they play a role in our subjugation by seeing us as victims, or seeing us as threats. The book is a way for us to get our voice out there,” she concluded.

![]()