- Tuesday, July 01, 2025

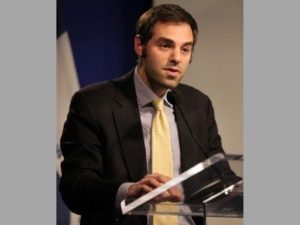

Many Pakistanis, including government officials, have previously accused Afghans of stealing Pakistani jobs and being involved in terrorism, says Michael Kugelman, an expert on South Asia.

By: Shubham Ghosh

PAKISTAN’S relations with Afghanistan have seen a slump in recent years and Islamabad’s decision to deport more than a million Afghan refugees has added fuel to the worsening ties between the two South Asian nations. The two countries, which remained longtime allies, have seen a deterioration in the situation two years after the Taliban returned to power in Kabul in August 2021.

Pakistan has blamed Afghanistan over a string of deadly terror attacks in its tribal region bordering the latter. With the elections due early next year, the Pakistani state is apprehensive over the country’s internal security. While it has extended the legal residence status for nearly 1.4 million Afghan refugees until December 31, it has refused to budge from its stance against stopping deportations of undocumented Afghans and other foreign nationals.

India Weekly spoke with Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center, Washington DC, who is a leading expert on South Asia, about the situation that is unfolding in one of the most volatile zones of South Asia, and other key issues related to Pakistan.

Here is what he told this news outlet:

India Weekly: Why do you think Pakistan has taken the decision to deport Afghan refugees at this particular time, particularly when a caretaker government is in charge of things?

Michael Kugelman: I’d actually argue that the reality of a caretaker government being in charge now is one of the main reasons why Pakistan chose to make the move when it did. It’s an apolitical and temporary administration, meaning that it won’t suffer any political blowback for having implemented a controversial policy. And at any rate, it is the military, which exerts heavy influence over the caretaker, which is driving this policy.

ALSO READ: Kugelman on the 50-over cricket World Cup and South Asia’s toxic nationalism

There are several other likely reasons why the move was made now. One is that there are compelling pretexts. Pakistan is going through one of its worst economic crises and terrorism resurgences in years. Many Pakistanis, including government officials, have previously accused Afghans of stealing Pakistani jobs and being involved in terrorism (they also have rightly pointed out that they have hosted large numbers of Afghan refugees for many years).

Given the current conditions in Pakistan, it is unfortunately an opportune moment to justify mass expulsions as an exercise meant to serve Pakistani economic and security interests. In reality, it’s more a massive exercise of scapegoating.

Another answer to the “why now” question is geopolitical. Pakistan is unhappy that the Taliban have not gone after anti-Pakistan terrorists based in Afghanistan, namely the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which is closely aligned with the Taliban. Islamabad likely is using the deportations as a pressure point, and a tool of leverage, hoping to pressure the Taliban into doing more to address Pakistani terrorism concerns. But given that Taliban leaders neither turn on militant allies nor respond well to pressure, it’s a tactic that’s likely to backfire.

India Weekly: To what extent could such a development impact Pakistan-Afghanistan relations and Pakistan’s internal security scenario, particularly when the elections are approaching and the country is facing major terror threats?

Kugelman: None of this will help Afghanistan-Pakistan relations, which have ironically taken a tumble since Pakistan’s longtime Taliban ally took power in Afghanistan. The Taliban won’t respond well to this move—it doesn’t want and cannot accommodate so many returnees.

The Afghan public, already bitter at the Pakistani state for sheltering the Taliban for many years and having long perceived that Afghans face discrimination in Pakistan, will not be happy either. And if Pakistan discovers—as it likely will—that this move won’t prompt the Taliban to help curb the TTP, then Islamabad’s unhappiness with the Taliban will intensify.

Additionally, with the Taliban not moving against the TTP and the TTP continuing to enjoy free rein in Taliban-led Afghanistan, terrorism risks will continue to rise in Pakistan, and especially with election campaigns providing tantalizing targets given the presence of big crowds. The TTP hasn’t targeted civilians as much in recent years, but election campaign events tend to attract large numbers of police and other security personnel, and they will be vulnerable.

India Weekly: Is the Pakistani state perceiving an existential threat at this moment, with its economy and internal security in doldrums and little political stability in sight? Or do you feel things can look up for the country after its next government takes charge?

Kugelman: It depends who you talk to. Of course, the military and the caretaker government are projecting strength and confidence. And they have reason to feel good. The military has things where it wants them: Imran Khan is jailed, and his party has been hollowed out and cut down to size. The military’s on-again-off-again, currently on-again, favourite son Nawaz Sharif is back in Pakistan and preparing to contest elections. The economy has stabilised somewhat, especially with new infusions of the International Monetary Fund’s funding.

But much of the Pakistani public feels very differently. In my two visits there this year, the most recent one in October, I sensed a level of skepticism and unhappiness that I haven’t discerned for many years.

The combination of political paralysis and polarisation, economic stress, terrorism threats, and the broader sense that it’s the same story playing out again and again that prevents the country from moving forward—all of this I think explains the unhappiness. Large numbers of people, including white-collar professionals, are leaving. Data from the government itself makes this quite clear.

In theory, things can look up if the election brings in a new government with a fresh mandate from the people. But with Khan’s party—probably the country’s most popular—weakened significantly, and with widespread worries about election rigging, there’s a good chance the election result won’t be accepted by a critical mass of the population. There will likely be a weak coalition government that is heavily exploited by the military, and for many Pakistanis that’s not a good outcome.

India Weekly: How big a role does the Pakistani military play now in the state affairs? Is it a force playing more from behind than in the past when its visibility in politics was high?

Kugelman: The military is playing a more overt role in policy than it typically does during periods of non-military rule. The military will always exert influence and veto power over security and foreign policy and many political matters. But it has historically played a more hands off role in other areas, including the economy.

But we are now seeing the army take on a leading role, on very visible levels, on economic policy. The army chief, for example, has a formal role in a new investment facilitation unit meant to expedite investment from the Gulf.

Every consequential policy decision now has a visible military role. The army chief attended the meeting that finalised the mass deportation move, for example.

I think the reasons are clear. The military got a bit spooked in recent months. Because of Khan’s large support base, the military’s popularity took a hit amid its major crackdown against Khan and the opposition.

When military facilities were targeted by protestors after Khan’s first arrest earlier this year, that had an effect on the institution too. The military is now keen to reassert its power. It also wants to maintain its efforts to weaken Khan, given the scale and duration of Khan’s criticism against the military prior to his being jailed. The military may give back some policy space in the months ahead, but only if and when it feels Khan and his supporters will be less of an issue.