- Thursday, May 09, 2024

The citizenship-activist said the practice of making political donations was there earlier but it was illegal.

By: Shubham Ghosh

ON March 14, India’s election commission unveiled in detail political donations worth millions of Indian rupees, a month after a five-judge bench of the country’s Supreme Court led by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud declared the contentious electoral bond scheme as “unconstitutional”. The verdict came following a series of hearings surrounding the scheme that the Narendra Modi government had launched in 2018 permitting anonymous donations to political parties.

The disclosure of the donations showed that the fundings heavily favoured the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), triggering a debate over transparency and fairness in politics in the world’s biggest democracy.

The matter that the revelations were made just a month ahead of India’s general elections added more fuel to the debate as the opposition cried foul targeting the ruling party. Rahul Gandhi, one of the country’s major opposition faces, called the scheme the world’s “biggest extortion racket”.

Critics argued that the anonymity of the donors would undermine transparency as the voters would remain uninformed over the source of money funding the parties and to what extent. Potential misuse of electoral bonds was also something they expressed concern over.

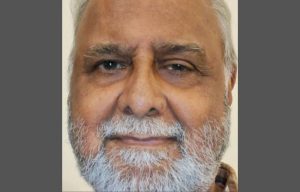

India Weekly spoke to Professor Jagdeep S Chhokar, one of the founding members of Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a non-governmental organisation in India that works on electoral and political reforms and was among those bodies that questioned the impact of electoral bonds could have on political accountability and transparency, on the development over electoral bonds.

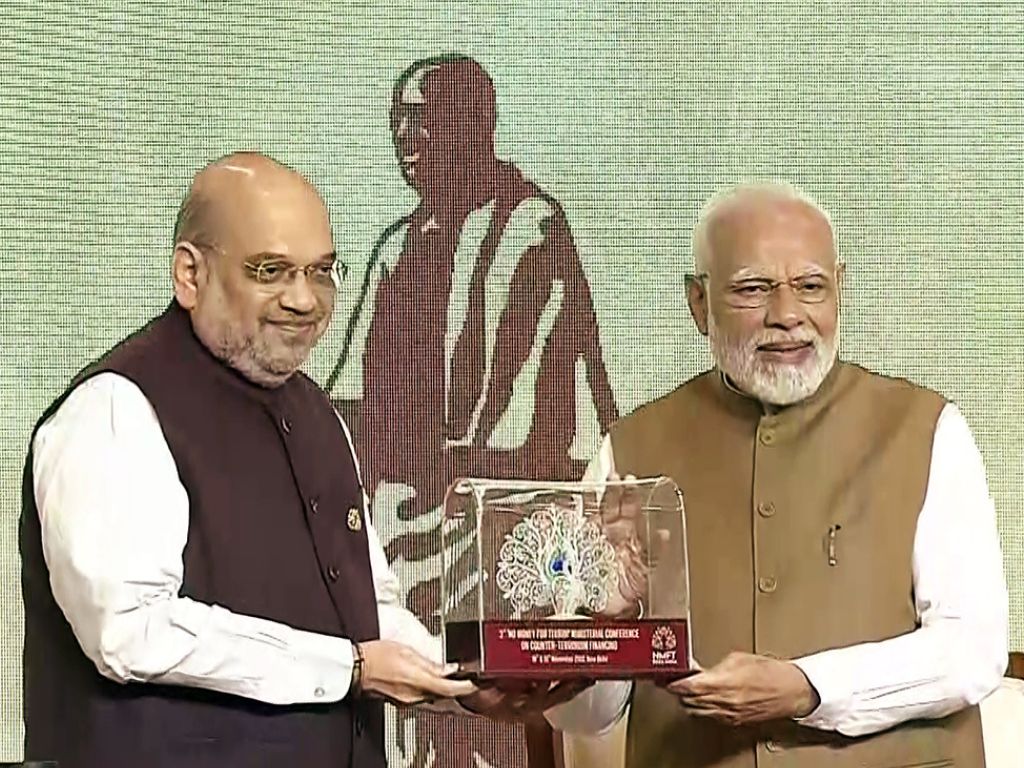

When asked about the implication of the electoral bond scheme and that some top leaders of the ruling dispensation, including home minister Amit Shah said the idea was to put an end to dominance of black money in Indian politics, Prof Chhokar said it might have been their interpretation but black money was never out of the political system even when the electoral bonds scheme was in operation.

Read: India electoral bonds: Top court asks State Bank of India to disclose details

“The Supreme Court declared the scheme ‘unconstitutional’ and it is mainly for two reasons. One, it disturbs the level-playing field of all parties in the democracy and secondly, it is against the voter’s fundamental right to information about the source of the money that political parties get ,” he said.

Read: India electoral bonds data released: From Lakshmi Mittal, Vedanta to lesser entities among buyers

“Black money was never out of the political system. It is coming through the banking system but from dubious sources,” he added. Prof Chhokar also said that illegal money stashed in tax havens abroad went through several countries till it reached a well-regulated system and then made an entry into the State Bank of India through the electoral bond. “Can we call it white money?” he asked.

But was not the practice of corporate fundings to political parties there earlier?

“The practice was there earlier as well but was considered illegal. Companies could use only 7.5 per cent of its average three-year net profit for political donations. That provision had been removed by the electoral bonds scheme . Massive amounts could be donated under the scheme and even loss-making companies could also make donations,” he said.

The ADR petitioned in 2017 to challenge the Finance Act, 2017, which was enacted as a money bill and introduced the bond scheme. It said under the scheme, a company is not required to name the parties to which donations are made and neither is the donor’s name revealed.

The watchdog feared that the amendments would lead to loss of transparency and breed corruption and increase circulation of black money besides creating shell companies and causing more unauthorised transactions to allow undocumented money to influence India’s political and electoral process.

The ADR also moved the Supreme Court on March 7 with a contempt plea against the SBI’s alleged failure to submit details of electoral bonds by the deadline of March 6 as prescribed by the apex court.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in the case has created a flutter. While it has allowed the opposition, that seemed listless even a few months ago, to accuse the ruling BJP of prime minister Narendra Modi of indulging in corruption, the business classes have also gone into a tense huddle.

On Monday (18), the top court refused to hear unlisted pleas from top industry bodies in India such as Associated Chambers of Commerce & Industry of India and Confederation of Indian Industry against disclosing bond details while asking the SBI, the country’s top lender, not to be “selective” while revealing all details of the now scrapped scheme by March 21.

It sought inclusion of the bonds’ unique alphanumeric and serial numbers and asked the election commission to “forthwith upload the data” on receipt from the bank.

Has the top court played a crucial role in the electoral bond episode? Prof Chhokar, while welcoming the top court’s verdict, also said that the ADR had filed the petition in 2017 and had the top court acted earlier, the practice could have been stopped much before.

“We would have been talking about Rs 1,000 crore (£94.6 million) instead of Rs 18,000 crore (£1.7 billion) as we are doing now,” he said.

Do electoral bonds set up a nexus between politicians and industrialists and encourage crony capitalism in Indian politics?

“Yes, it certainly does,” the citizen-activist said, adding that the picture will get clearer on March 21 when more details about the bonds will be revealed. According to Prof Chhokar, it would be known which company gave how much money to which party and information about possible quid pro quo would also be unearthed.

Data has shown that the BJP was the single biggest recipient by far in the period between April 2019 and January 2024. It had received slightly less than 48 per cent of all bonds cashed by parties up to March last year, amounting to nearly Rs 7,000 crore (£663 million). The Trinamool Congress, ruling party of the eastern state of West Bengal and a member of India’s opposition Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, received Rs 1,397 crore (£132.2 million). The Congress was in the third spot with Rs 1,334.35 crore (£126.3 million).

The Bahujan Samaj Party, a key player in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh and three Indian Left parties — the Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation said they haven’t received any money through electoral bonds.

Prof Chhokar also said that ADR had challenged the electoral bonds scheme on the ground that it was included in the budget which was a money bill whereas the electoral bonds scheme did not qualify as a money bill issue. The Supreme Court does not include this particular issue in its hearing and reserved it for consideration with some other petitions pertaining to money bills. He said it is possible that the electoral bonds scheme may well be declared unconstitutional even on that count separately.

The activist, however, refused to comment when India Weekly asked him whether the electoral bonds scheme episode will have an impact on the general elections beginning on April 19.

“We did not approach the court to defeat any particular party or to make any particular party win. Our only aim is to bring transparency in the system. The general elections of 2019 were not very far when we had petitioned the matter in the top court but no question was raised at the time. We only asked the court to declare the scheme unconstitutional since we felt it undermined transparency in our democracy. Now, whether the latest developments will impact the 2024 election or not is something I can’t comment on,” he said.

![]()